My Adventure with a Finicky Light Meter

So, I was out shooting the other day, you know, with my trusty old film SLR. Love these things, built like tanks. But man, my pictures were coming back looking all sorts of wrong. Some were blown out, others dark as a dungeon. Figured the light meter was acting up again. It’s a common thing with these older cameras, they drift, or someone before me messed with it.

Figuring Out the Problem

First, I had to be sure it was the meter. I mean, it could’ve been my developing, or maybe I was just having an off day. So, I did a simple test. I grabbed my digital camera, which I know has a pretty accurate meter, and also downloaded one of those light meter apps on my phone. Not perfect, mind you, but good enough for a baseline when you’re in a pinch.

I pointed all three – the SLR, the digital, and the phone app – at the same boring, evenly lit wall. My living room wall, to be exact, nothing fancy. Didn’t want any tricky shadows messing things up. And yup, the SLR was way off. Like, it was telling me to overexpose by nearly two stops compared to the others. No wonder my skies were always just a white blob!

The “How To” Part – My Way, No Guarantees!

Alright, so how did I go about fixing it? Lemme tell ya, it’s not always the same for every SLR, these old beasts all have their quirks, but the general idea is usually similar. Here’s what I ended up doing:

- Finding the adjustment spot: This was the real treasure hunt. On some cameras, like an old Pentax K1000 I once wrestled with, there’s a tiny little screw, they call it a potentiometer, often hiding near the ISO dial or sometimes you gotta peek inside where the film rewind knob is. You might need to gently pop off a cover. My current workhorse, a Nikon FM2, has its own secrets, but for a real deep calibration, it’s often an internal thing. I really had to dig around online, looking for old forum posts or, if I got lucky, a blurry PDF of a service manual. You gotta be super careful here, don’t just go poking around with a screwdriver willy-nilly.

- Getting a reference point: Like I said, I used my digital camera that I trust. And a handheld meter can be good too. I made sure to set the ISO on my SLR to match whatever I was using as my reference. Let’s say I set both to ISO 400.

- Pointing and comparing notes: Then, I pointed both the SLR and my digital camera at something plain and evenly lit. A proper grey card is what the pros use, but honestly, my boring beige wall did the job. I was just looking for a nice middle grey area.

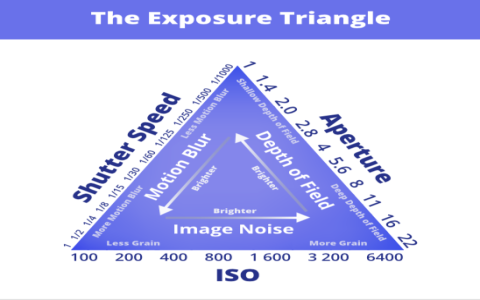

- Matching up the settings: I’d pick an aperture on the SLR, say f/8, just a common one. Then I’d look through the SLR’s viewfinder to see what shutter speed its meter was suggesting for a good exposure. After that, I’d check my digital camera – what shutter speed was it suggesting for that same f/8, at ISO 400, looking at the exact same spot?

- The Tweak-a-thon: If they didn’t match (and they didn’t, not by a long shot at first), this is where the real delicate surgery began. With a tiny, tiny screwdriver, I’d give that little potentiometer the slightest turn. And I mean slight. Like, imagine a snail trying to turn it. Then I’d check the meter reading in the SLR again. Still off? Okay, another microscopic nudge. It’s a real back-and-forth, a game of patience. You push it a tiny bit one way, it might jump too far, so you nudge it back. It’s a bit like trying to tune an old radio, you know? Small, careful adjustments.

Super important thing I learned the hard way: I always, always make sure the battery in the SLR is fresh before I even think about starting this. A weak or dying battery can make the meter readings go completely bonkers, and you’ll be there all day adjusting something that ain’t the real problem, just chasing your own tail.

So, Did All That Fiddling Work?

After a fair bit of squinting, careful turning, and checking, maybe a good 20 minutes of this delicate dance, I finally got the SLR’s meter to give me pretty much the same shutter speed reading as my digital camera. Same scene, same aperture, same ISO. Felt like I’d cracked a code!

I then double-checked it in a few different lighting conditions, just to be sure it wasn’t just a fluke. Pointed it at something brighter, then something a bit darker. Seemed to hold up pretty well. The real proof, of course, was sacrificing a roll of film to the cause. Shot a test roll, got it developed, and what do you know? The exposures were worlds better. Finally, my pictures started looking a heck of a lot more like what I actually saw and intended to capture.

Why Even Bother, You Might Be Thinking?

You might be sitting there thinking, “Man, why go through all that headache? Just use an app on your phone or carry a separate light meter all the time.” And yeah, you absolutely could do that. Plenty of folks do. But for me, there’s something really satisfying about getting the camera itself to work the way it was designed to. These old machines, they were built with everything you needed, and often a little bit of understanding and a careful tweak is all they need to sing again. Plus, let’s be honest, it’s just plain convenient to have a working built-in meter when you’re out trying to catch a shot. It’s like, I don’t want to juggle three different gadgets just to take one picture. I want the camera to be the complete tool. And now, this old dog does its job again. It’s not some kind of high-tech wizardry, just a bit of practical hands-on effort. And honestly, it feels pretty darn good to fix something yourself, you know? These things have soul.